30 Mar Treasures of the earth – part 1

What makes a great find? There are a number of ways that finds can stick out. Some are very rare, some very beautiful. Sometimes a find in remarkably good condition will cause some excitement – a complete pot, for example, will always turn more heads than a few broken sherds. Sometimes quite ordinary finds become extraordinary at a particular site by an unusual and remarkable weight of numbers. Sometimes they are very evocative of past times and past lives or tell particularly vivid or poignant stories.

Our finds manager, Julie Franklin, who has been at Headland since 2005, and before that worked with Headland finds on a freelance basis, was ideally placed to choose the greatest finds from Headland’s history. Choosing favourites from such a long list of disparate objects was somewhat difficult but here is Part 1 of her list, finds 1 to 10, in no particular order.

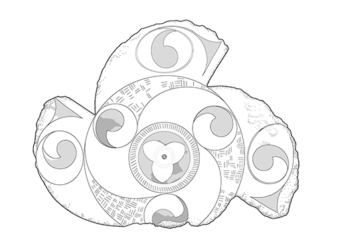

Copper alloy and enamel harness mount, early 1st century AD, Doune Roman Fort, Stirlingshire

Originally with four arms, it is decorated in a style typical of southern England with incised lines and red enamel infill. Its dating means that it must have been an heirloom by the time it travelled this far north in c AD 80, possibly with a soldier recruited in the south.

Ceramic bronze-casting mould for a sickle, late Bronze Age, Bellfield and Lettoch Farms, North Kessock, Highland

This site produced a nationally significant collection of well-preserved bronze-casting moulds from securely dated contexts. Over 150 mould fragments were found, including a number of moulds for sickles, axeheads, gouges, knives and spearheads. The sickle moulds were particularly significant as finds of late Bronze Age bronze sickles are extremely rare in Scotland.

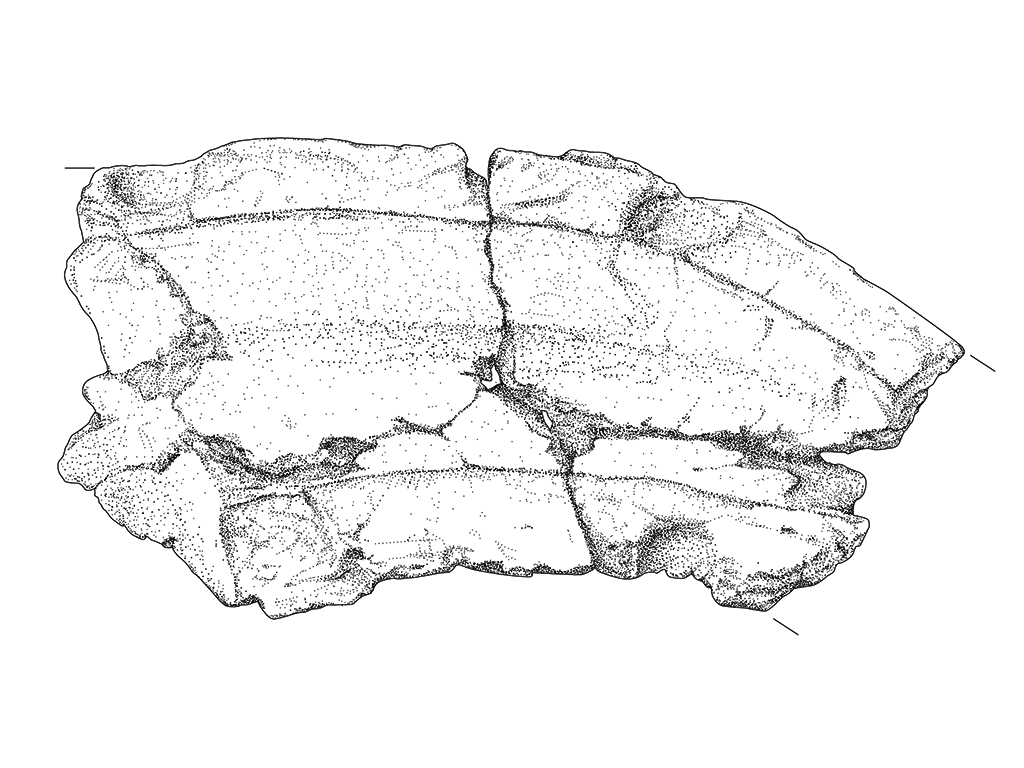

Grooved ware, late Neolithic, Powmyre Quarry, Glamis, Angus

Prehistoric pot sherds are rarely this size. It is 175 x 180mm and makes up most of the profile of a grooved ware pot, decorated with incised lines and applied strips. It has been argued that the design of some Grooved Ware pots may mimic wicker baskets and this example has been held up as a particularly convincing example complete with the cross-hatching between the vertical ribs. You can read more on the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework’s Neolithic Panel Report, page 97.

Glass bead, 2nd century BC-1st century AD, near Deddington, Oxfordshire

The larger bead on the left was found in a 4m wide pit containing articulated human remains. The bead itself is very large at 29mm in diameter. It is of clear translucent glass with an opaque yellow trail inside the perforation. When viewed from the side the yellow trail shines through and creates a soft glow. The type has a southern English distribution and they are probably continental imports. It is possible that it accompanied the burial. Though relatively rare finds, we found the smaller bead on the right, serendipitously, at a completely different site in Gloucestershire about two weeks later.

Iron dividers, 18th or 19th century, Cathedral Close, Hereford

These dividers were found in the coffin of a young man. While these may have been a tool of the man’s trade in stonemasonry or woodworking, it is possible that he was in fact a freemason and was buried with masonic regalia. Though there is no evidence that this was practiced, there was a local record of a masonic funeral in the town, with a procession preceded by a military band and members of the lodge. The coffin is recorded as having ‘regalia on top of the pall’. You can buy the book to find out more (amazon link).

Copper alloy book mount, 16th or 17th century, Cathedral Close, Hereford

The book clasp is beautifully made and decorated with diagonal hashers, rings, pierced holes and wheatear motifs. Book clasps were riveted to the bindings of books to secure them shut. The fish tail end of this example is fairly typical of 16th and 17th century examples. It was found in the general graveyard soil in St John’s Quad, just outside the Cathedral but is in remarkably good condition, with the remains of a leather strap still sandwiched between the two plates. It conjures a vision of one of the Vicars Choral scurrying from his lodgings to work at the Cathedral with his battered religious text shedding its clasp along the way. You can buy the book to find out more.

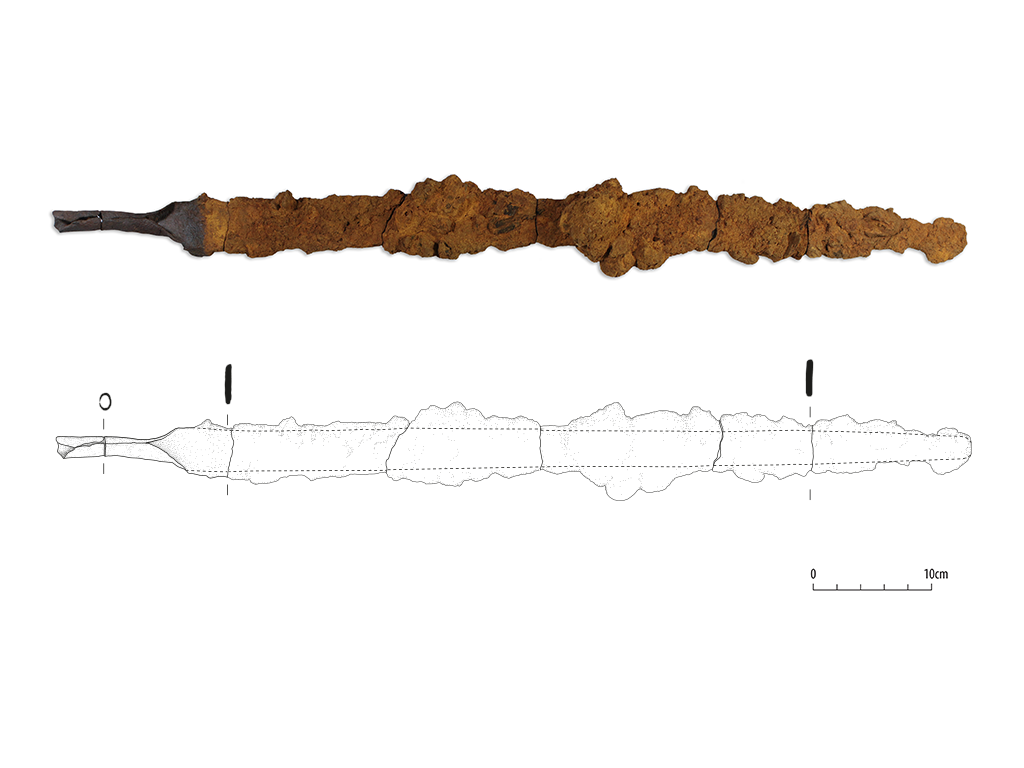

Iron sword-shaped currency bar, 2nd-1st century BC, Commonhead, Swindon, Wiltshire

This caused some excitement when first found as it appeared to be a sword. But on closer inspection, the ‘hilt’ end was all wrong and it wasn’t in any way sharp or pointed. It is in fact a type of iron ingot. The end of wrought into the shape of a socketed tang to demonstrate the quality of the iron. It is nearly 90cm long and contains almost a kilogram of iron and would have been of some considerable value at the time. It was apparently ritually deposited in the terminus of a ring-ditch.

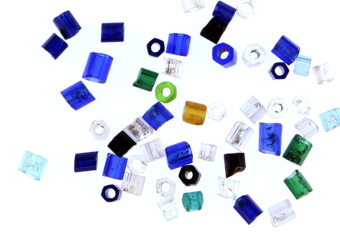

Glass drinking vessel, first half of the 17th century, Greyfriars Kirkhouse, Candlemaker Row, Edinburgh

This was a remarkable survival, albeit with the lower half of the vessel missing. It was found stuffed down a drain outside a 17th century tenement. Its combination of moulded and painted decoration of hearts and flowers is, as far as we know, unique and it may have been imported from the Netherlands or eastern France.

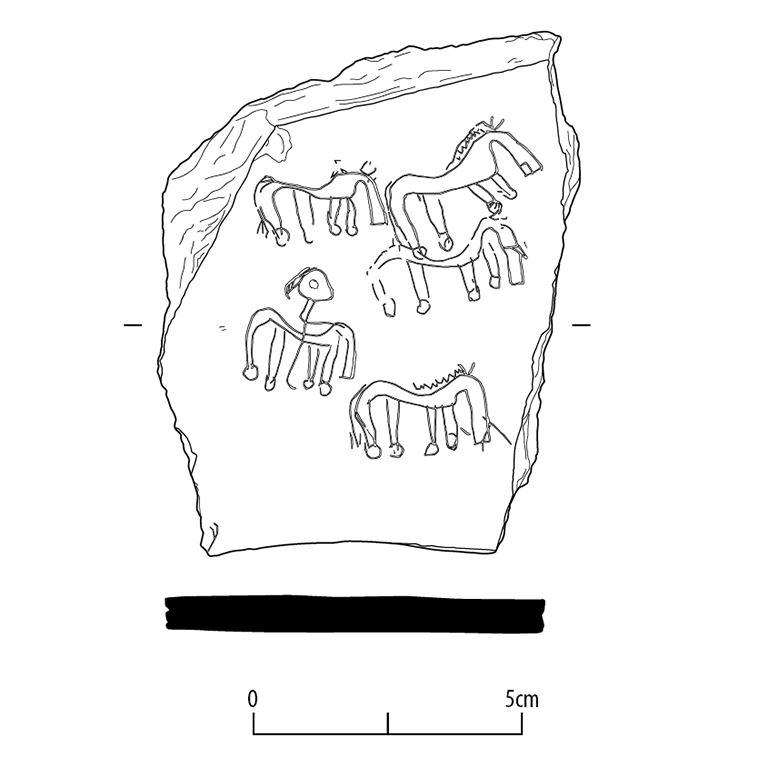

Incised slate, AD 750-1000, Inchmarnock, Firth of Clyde

The incised slates of Inchmarnock have already been covered in a Headland hightlight (link), but no summary of Headland’s greatest finds would be complete without them. The hostage stone and the slates inscribed in ogham and latin scripts are of national importance and much has been written on them. Here, however, is Julie’s favourite, featuring a child’s drawing of horses. It is a reminder that some things don’t change that much, even over a thousand years. You can buy the book from us to find out more.

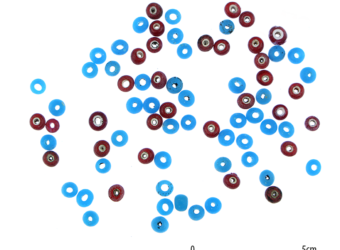

Glass beads, c 1820-60, St Peter’s Church, Blackburn

Many of the graves contained small glass beads which seem to have been worn as necklaces. This in itself was not remarkable as bodies of this period are sometimes dressed in clothes they would have worn in life including jewellery and the phenomenon of the use of glass beads in burial, particularly infant burials has been noted elsewhere. But at Blackburn it was found in unprecedented levels. The final total was 20,000 beads, with over a quarter of the infant graves containing glass bead jewellery. We still don’t fully understand why, though there is other evidence from the site that particular care and attention was exercised in the burial rites when children died so tragically young.