10 Jan A Wild West (Coast) Adventure (In The Firth Of Clyde)

‘Great projects, amazing locations and a great team of archaeologists are what make all the difference, and if the project can make a substantive contribution to our understanding of the past, then so much the better. Inchmarnock was one of those projects: an uninhabited island, a daily commute by RIB in what were often interesting seas and, with a range of archaeological sites to be investigated, what was there not to like? Apart from the midges, of course ….’

Inchmarnock is a small island off the west coast of Bute in the Firth of Clyde. Between 2000 and 2004 we undertook a wide-ranging programme of survey and excavation of multiple sites throughout the island. Among the sites investigated was a rock shelter with Late Iron Age and early medieval occupation deposits, a series of medieval corn-drying kilns, and a building platform on which a 17th-century turf-built longhouse was erected, masking medieval and early medieval activity on the same site. But the key site to understanding the island’s early medieval and later history is the site of the 12th-century church.

The Early Christian origins of the site have long been recognized as a result of the discovery here from time to time of early cross slabs. Radiocarbon dates now clearly indicate activity on the site from around at least the third quarter of the first millennium AD. We also found evidence of a late medieval literate presence, possibly associated with the regulation of pilgrimage activity on the island.

The 2000-2004 excavations have not only identified what is probably an earlier stone-built church on the site but also the remains of a much earlier monastic settlement, specifically the detritus associated with a school-house where novices were taught how to read and write, as well as compass-work and instruction in elementary design and decoration. As discussed in the published monograph, this marks a major break-through in terms of our understanding of how education was organised at this time.

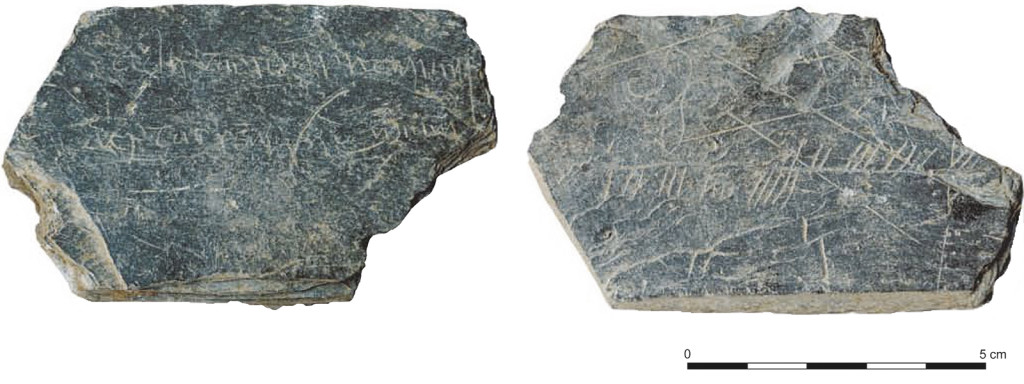

The incised and inscribed slate fragments from Inchmarnock is the largest assemblage of such material from the British Isles. It includes examples of script, sketches of boats, buildings, animals and people, as well as geometric motifs, doodles and scribbles. It is of particular importance because of its implications for monastic schooling and design, as well as providing an insight into the age of the scholars whose handiwork we now have. The sketch drawings would be consistent with the work of children of primary school age, possibly 7 – 11 or thereabouts. The age of the scholars also provides an insight into the practice of fostering. This was a familiar feature of early Irish secular society and was quickly seized upon by the early Irish Church as a means of providing income and extending its influence.

The incised and inscribed slate fragments from Inchmarnock is the largest assemblage of such material from the British Isles. It includes examples of script, sketches of boats, buildings, animals and people, as well as geometric motifs, doodles and scribbles. It is of particular importance because of its implications for monastic schooling and design, as well as providing an insight into the age of the scholars whose handiwork we now have. The sketch drawings would be consistent with the work of children of primary school age, possibly 7 – 11 or thereabouts. The age of the scholars also provides an insight into the practice of fostering. This was a familiar feature of early Irish secular society and was quickly seized upon by the early Irish Church as a means of providing income and extending its influence.

Epigraphic evidence suggests that some of the inscriptions could date to the early 7th century. One of the earliest pieces, recovered from the monastic enclosure ditch, is a rough water-worn slate cobble, possibly a prayer-stone, on which the name Ernán – the Gaelic familiar form of the saint’s name, Marnock – has been written no fewer than three times. Meanwhile, from the metal-working area near the church came a fragment of an incised slate board datable to around 750. On one side was a curvilinear cross-motif, set beside an ogham alphabet; on the other side were two lines of almost identical Latin text, identifiable as a line of octosyllabic Hiberno-Latin verse: adeptus sanctum praemium, ‘having reached the holy reward’. This is a unique survival, a line of verse from a hymn that formed part of the Antiphonary of Bangor, a late 7th-century liturgical commonplace book and clearly one that was on the ‘Inchmarnock curriculum’. The same stone also gives us our first evidence for the informal, non-monumental use of ogham alongside Latin, and moreover provides clear evidence of training and instruction in both

But perhaps the most iconic image of all was the so-called ‘Hostage Stone’, which was found as two conjoining pieces, roughly 4m and a year apart, in 2001 and 2002. The stone appears to depict three armoured warriors leading a fourth figure off to their boat. The warriors are marked out by their chain-mail armour, their weapons and their generally wild appearance; the fourth figure, however, appears to be dressed differently and holds in front of him what may be a house-shaped reliquary shrine or silk reliquary purse. Presumably the reliquary defines the figure’s ecclesiastical office, in much the same way as the mail armour and weapons define his abductors. Although not necessarily ‘Viking’, the image nonetheless speaks volumes for the dangers that would have been ever-present to island-dwellers in the Firth of Clyde in the last quarter of the first millennium AD.

This is a key site and the inscribed slate assemblage is nationally important, not only for what it can tell us about the chronology of the inscriptions themselves but also the cultural connections of Ernán’s foundation; clearly, Inchmarnock looked to the Gaelic west rather than the Brittonic east, with its seat at Dumbarton. The school-house also gives us a clear focus for the function and status of the monastic settlement and its role as a place of primary schooling. This was a place where the very basics of literacy, of practising alphabets and controlling the stylus, were taught. Without these basic training schools there would have been no Book of Kells, nor any of the other great illuminated manuscripts of early Insular Christianity.

The challenge for the future will be to identify the sites and settlements which would have formed the intermediate links in this chain, between primary, secondary and tertiary levels of instruction and training.

The results of the project were published in September 2008 in the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland monograph series. Copies are available from our our Amazon Shop.

The project – from conception through to publication and archive – was commissioned and fully funded by Lord Smith of Kelvin, the island’s owner.

The Project was Highly Commended in the ‘Best Archaeological Project’ category at the 2010 British Archaeology Award.